NUESTRO REPORTAJE PARTICULAR

Cornelia I. Toelgyes

1 de diciembre de 2013

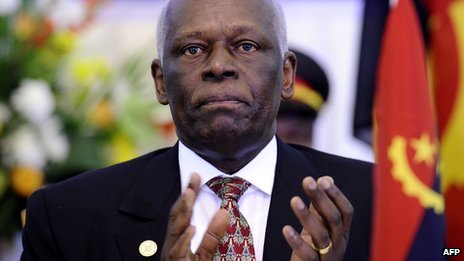

Josè Edoardo dos Santos nace en 1942 en un barrio pobre de Luanda (Angola). Él sabe lo que significa la represión: se matricula siendo muy joven en el MPLA (Movimiento Popular para la Liberación de Angola) y en 1956 el gobierno colonial lo obliga a exiliarse. Primero en Francia, después en el Congo, y finalmente se traslada a Rusia, donde termina sus estudios como ingeniero. Vuelve en su país en 1970 y, después de la independencia de Portugal, en 1975 se convierte en ministro de Relaciones Exteriores. En 1979, tras la muerte de Agostinho Neto, es elegido como presidente, cargo que sigue ocupando hoy día.

Angola, se estrechan las mallas del régimen. El Presidente Dos Santos se ha olvidado de cuando era pobre y en el exilio

Angola, si stringono le maglie del regime. Il presidente Dos Santos si è scordato di quand’era povero e in esilio

NOSTRO SERVIZIO PARTICOLARE

Cornelia I Tolgies

1 dicembre 2013

Josè Edoardo dos Santos nasce nel 1942 in un quartiere povero di Luanda (Angola). Sa cosa significa la repressione: si iscrive ancora giovanissimo all’ MPLA (Movimento popolare di liberazione dell’Angola) e nel 1956 il governo coloniale lo costringe all’esilio. Dapprima in Francia, poi in Congo e per ultimo si trasferisce in Russia, dove termina gli studi come ingegnere. Torna nel suo paese nel 1970 e, dopo l’indipendenza dal Portogallo, nel 1975 diventa ministro degli esteri. Nel 1979, dopo la morte di Agostinho Neto, viene scelto come presidente, carica che ricopre ancora oggi.

Aereo mozambicano con 34 persone a bordo si schianta in Namibia: nessun sopravvissuto

DAL NOSTRO INVIATO SPECIALE

Massimo A. Alberizzi

Windhoek, 29 novembre 2013

Un aereo mozambicano con 34 persone a bordo (28 passeggeri e sei membri dell’equipaggio) si è schiantato in Namibia: nessuno è sopravvissuto. I resti del velivolo sono stati trovati nel parco nazionale Bwabwat nel dito di Caprivi, quel territorio dove una striscia di territorio namibiano si incunea tra l’Angola e il Botswana. Non si conoscono la cause del disastro, “E’ troppo presto per poter trarre delle conclusioni – ha spiegato ai giornalisti uno dei dirigenti della polizia di Windhoek. Prendiamo comunque in considerazione anche l’ipotesi attentato. L’aereo si è completamente distrutto, bruciato e ridotto in cenere”, ha spiegato.

Arrestato in Mali l’assassino di un diplomatico americano in Niger

NOSTRO SERVIZIO PARTICOLARE

Cornelia I. Toelgyes

29 novembre 2013

L’FBI ci ha messo 13 anni per mettere le mani su Alhassane Ould Mohamed, detto Cheibani, il killer di un diplomatico USA (William Bultemeier), ucciso a sangue freddo a Niamey (capitale del Mali) mentre usciva da un ristorante nel dicembre del 2000.

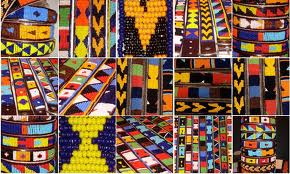

Artigianato keniota al mercato benefico prenatalizio a Milano

Milano, 29 novembre 2013

Come ogni anno, sabato 30 novembre e domenica 1 dicembre torna alla Basilica di San Carlo al Corso a Milano, ingresso da Corso Matteotti 14, il mercatino benefico “Suk de Noël”: una ricca selezione di pezzi di artigianato africano ricercati e originali tra cui scegliere un regalo solidale.

Kenya, il presidente Kenyatta si rifiuta di promulgare la legge bavaglio sulla stampa

DAL NOSTRO INVIATO SPECIALE

Massimo A. Alberizzi

Nairobi, 28 novembre 2013

I deputati kenioti hanno tentato di ancora una volta di mettere il bavaglio alla stampa ma non ci sono riusciti. Hanno approvato una legge capestro che, di fatto, prevedeva il controllo della politica sulla libera informazione, ma il presidente Uhuru Kenyatta ha posto, per la prima volta da quando è stato eletto nell’aprile scorso, ha posto il suo veto: niente da fare, le nuove norme si scontrano con la Costituzione.

In meno di due anni da capitano golpista a generale presidente e ora in carcere: la parabola del maliano Sanogo

DAL NOSTRO INVIATO SPECIALE

Massimo. A. Alberizzi

Nairobi 28 novembre 2013

Era un semplice capitano dell’esercito Amadou Haya Sanogo il 22 marzo 2012 quando con un colpo di Stato si impadronì del potere e si autoproclamò presidente del Mali. Poco dopo si regalò i gradi di generale e oggi è stato arrestato con accuse gravissime: omicidio, tortura, stupro, sequestro di persona, intimidazione e violenze di vario genere contro gli oppositori politici o chi non la pensava come lui, specie tra i militari.

Repubblica Centrafricana nel caos, si rischia un nuovo genocidio. La Francia invia truppe

DAL NOSTRO INVIATO SPECIALE

Massimo A. Alberizzi

Nairobi, 27 novembre 2013

La Repubblica Centrafricana (CAR, dall’acronimo inglese, Central African Republic) rischia di diventare una nuova Somalia. Guerra perenne tra bande con la popolazione civile che ne fa le spese. Che possa discendere nel “più completo caos” è stato sottolineato dal vicesegretario delle Nazioni Unite Jan Eliasson, che ha chiesto al Consiglio di Sicurezza di agire immediatamente, trasformando l’attuale contingente dell’Unione Africana (2500 uomini) in un’operazione di peacekeeping dei caschi blu.

Eritrea violenta: l’inferno di Elsa, Lula & le altre a Sawa, il campo degli stupri

Dalla Nostra Inviata Special

m. r.

Asmara, 26 settembre 2002

E’ da poco passata la mezzanotte. Svegliata dai colpi prepotenti sferrati con il calcio del fucile contro la porta di casa Lula, terrorizzata, schizza all’improvviso dal letto. La diroccata palazzina di due piani nei pressi dell’aeroporto di Asmara è circondata dai soldati. La ragazza infila velocemente un pantalone e un giubbotto, e prima di aprire la porta volge un rapido sguardo verso gli occhi disperati di sua madre. L’ufficiale sull’uscio ringhia qualche frase verso le donne. Lula il menqesaqesi, il tesserino militare, non ce l’ha.

Un uomo l’afferra con violenza per il braccio e la trascina su un camion, già carico di ragazzi e ragazze impauriti. In pochi secondi il mezzo sparisce nell’oscurità. Destinazione Sawa, un durissimo e inavvicinabile campo militare di addestramento situato nell’infuocato deserto ai confini con il Sudan.

Le giovani eritree lo chiamano più semplicemente, sussurrandoti nell’orecchio, il “campo degli stupri”. Nell’accampamento ci passano tutti, prima o poi. È la tappa obbligatoria degli eritrei tra i 17 e i 40 anni, ma spesso ci finiscono ragazzine e ragazzini di 15 e 16 anni. Le cifre sono agghiaccianti: si calcola che oltre 200 mila eritrei, la metà donne, siano stati reclutati forzatamente. Quando Lula entra a Sawa è il gennaio del 2001. Ha da poco compiuto 17 anni, ha lasciato la scuola nel 1998 per occuparsi della sorella minore.

Sua madre, abbandonata dal marito, è malata di cuore. Dei due fratelli maggiori non si hanno più notizie da oltre due anni. Come altri 19 mila giovani saranno morti durante l’insensata guerra contro l’Etiopia scatenata nel 1998. Per Lula i sei mesi trascorsi nel maledetto accampamento sono ancora un incubo. Racconta: “All’inizio è stata una tortura. Ho sopportato in silenzio lunghe marce a piedi nel deserto, tra i ragni e i serpenti sotto un sole accecante che ti spezza le gambe. Volevo dimostrare ai “capi” che sono una brava patriota. La sofferenza è cominciata quattro mesi dopo, quando ero troppo stanca per ribellarmi. Gli uomini, al tramonto, entravano prepotentemente nella tenda e sceglievano una di noi per passare la notte. Si trattava di ufficiali, anche sposati, che consideravano normale portarsi a letto ogni sera una soldatessa diversa. Sono rimasta quasi subito incinta e mi hanno immediatamente rispedita a casa”.

La drammatica esperienza di Sawa ha significato per la giovane mamma l’abbandono di ogni speranza nel futuro. “La propaganda di governo promette posti di lavoro a 150 nakfa al mese, circa 7,5 euro al cambio nero, ai giovani che tornano dal servizio militare obbligatorio, ma non è vero. Ci impediscono di studiare e ci rubano i sogni. Quando finirò di allattare Stella, senza un marito, non so come la sfamerò. Ma una cosa è certa: quando sarà il suo turno la nasconderò. La mia bambina non andrà mai a Sawa”. Alcune suore, in segreto, gestiscono una clinica per ex soldatesse. Molte famiglie non riaccolgono più in casa le ragazze madri o quelle che riescono a fuggire da Sawa. Le religiose diventano così le uniche confidenti di giovani donne traumatizzate o in procinto di partorire figli concepiti nei campi militari.

“La situazione è ormai incontrollabile”, sostiene una suo-ra. “Moltissime donne sposano perfetti estranei per evitare i “giffa”, i rastrellamenti forzati. Altre non reggono e si suicidano. Da quando il governo ha deciso di non reclutare più donne con figli, in clinica abbiamo fatto il pieno di ragazze che aspettano bambini da sconosciuti. Poi tornano disperate quando si rendono conto che senza tesserino militare non avranno mai un lavoro. L’avvenire di questo Paese è nero”.

Elsa, invece, i suoi 18 mesi di servizio militare se li è fatti tutti. Compresi 12 terribili vicino ad Assab, nell’inferno del deserto dancalo. Mostra foto sbiadite di Sawa, durante l’addestramento, lei fiera nella mimetica, è sorridente. “Era il 1998, avevo 20 anni. Dopo sei mesi ho capito che quei soldati mi chiedevano un “servizio” diverso. Io e la mia compagna di 17 anni siamo finite in una casa con militari uomini”, sussurra Elsa. “In pratica siamo diventate le loro serve. Dodici ore al giorno di lavoro e stuprate la notte: un tormento insopportabile. A me è toccato un uomo non sposato, all’inizio ero contenta ma poi quando sono rimasta incinta mi ha rispedito ad Asmara. Per fortuna è successo due mesi prima dello scoppio della guerra, altrimenti sarei morta al fronte. L’ufficiale mi scrisse una lettera: per dirmi che il figlio non era suo. So che si è sposato con un’altra. Molte mie compagne si sono ammalate di Aids. Sappiamo che esiste questa malattia, ma io non so bene come si prende”.

La corsa del virus in Eritrea è allarmante: nel 1988 appena un caso, nel 2001 oltre 13.000 ammalati, 3.000 in più ogni anno. La guerra tra Eritrea ed Etiopia è finita da un pezzo. 3.500 caschi blu delle Nazioni Unite, tra cui 150 italiani, sorvegliano il cessate il fuoco. Il presidente Isaias Afeworki aveva promesso solennemente di smobilitare circa 150 mi-la soldati e, con i fondi della Banca Mondiale, favorire le attività professionali e di studio. Del progetto, oggi, nessuno ne parla più. Ogni notte agli angoli delle strade soldati ragazzini, in tuta mimetica e sandali, intimano ai loro coetanei di esibire l’odiato mengesagesi. Chi ne è sprovvisto finisce direttamente a Sawa. Vietato parlare di reclutamenti forzati. Il governo preferisce chiamarli “programmi di lavoro estivi”, o “maetot”, servizio di leva obbligatorio. Da giugno di quest’anno i rastrellamenti si sono intensificati, fino a raggiungere i tremila nella sola notte del 9 luglio. La sera le strade di Asmara sono quasi deserte. Gli unici giovani che frequentano bar e ristoranti sono i “beles”, i fichi d’india, come vengono chiamati affettuosamente da queste parti gli emigrati che tornano in Eritrea per trascorrere le vacanze estive. Per sfuggire ai reclutamenti forzati le ragazze dormono ogni sera in luoghi diversi, oppure, come le cameriere degli alberghi, si fanno rinchiudere nelle cantine già attrezzate di materassi e acqua.

Ma spesso non basta. Gli ufficiali dell’esercito si presentano direttamente al datore di lavoro per esigere la consegna del personale. I rastrellamenti hanno provocato la paralisi dell’economia e, di conseguenza, molte imprese hanno chiuso i battenti. Se gocciola un rubinetto non ci sono idraulici per ripararlo, la terra coltivabile è trascurata perché non ci sono braccia giovani e forti, il ministero dell’Educazione ha dovuto assumere 300 insegnanti indiani, perché quelli eritrei sono spariti al fronte o spediti a Sawa. Il presidente Isaias, che non ha mai promulgato la costituzione del 1997, recentemente ha fatto arrestare – in una località segreta – 15 dei suoi più stretti e illuminati collaboratori. Avevano “osato” scrivere una lettera dove si richiedevano le riforme democratiche che tutti i cittadini aspettano da tempo.

La stampa libera è stata soppressa e i giornalisti incarcerati. 400 studenti universitari che si oppongono ai “campi di lavoro estivi” sono stati spediti a Wia, un lager vicino al porto di Massaua dove le temperature superano spesso 40 gradi, con il compito di ammucchiare pietre. Ad altri 1.700 è stato impedito di iscriversi al nuovo anno accademico, perché bloccati in un interminabile servizio militare obbligatorio. Parlare apertamente della situazione politica e sociale del Paese è impossibile.

Come negli anni ’70 e ’80 è ricominciato l’esodo. Moltissime donne scappano: in Etiopia, in Sudan o via mare. Chi può pagare, viene trasportata sulla costa e sistemata su una piccola imbarcazione nel bel mezzo del Mar Rosso, in attesa che arrivi una nave più grande in rotta verso l’Europa. Altre cadono vittime di truffatori senza scrupoli. In Eritrea i legami con l’Italia sono ancora molto forti. Tantissimi eritrei, anche giovani, parlano perfettamente la nostra lingua. Ad Asmara c’è la più importante scuola italiana all’estero e l’architettura anni ’20 della città, come anche l’atmosfera che si respira, è quella di una tranquilla e sonnacchiosa cittadina del nostro sud.

Una sera, in un ristorante, davanti a un fumante piatto di tagliatelle al ragù, un eritreo sulla cinquantina accetta di parlare di sua figlia, ma si capisce che lo fa con imbarazzo. “Ha vent’anni. Ha finito la scuola italia-na due anni fa, anche sua nonna – mia madre – era italiana. Dovrebbe partire per Sawa, ma le ho procurato dei documenti falsi dove risulta che è ancora troppo giovane. Partire per l’estero? Impossibile: senza tesserino militare, niente passaporto. Il governo ha perfino annullato tutte le borse di studio, perché molti studenti non tornavano più. La sera non esce e tutta la famiglia la sta nascondendo per proteggerla dall’aberrante campo militare. Ma in questo Paese di poco più di tre milioni e mezzo di abitanti, non ci sono più tanti posti per nascondersi”.

m.r.

Questo articolo è stato scritto nel 2002 ma è ancora valido

It is possible to read this article also in English

Violence against women: the hell of Elsa, Lula & the others at Sawa, the rape camp in Eritrea

OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT

m.r.

Asmara, September 26th 2002

Wearisome march performed under a burning sun, amid poisonous spiders and snakes is what the young girls that the Government in Asmara mops up can expect to do for 18 months. To be near the mark, however, the reality is more dreadful. As a matter of fact, they are actually made to wait upon male solders, particularly military officers, for 12 hours per day and during the night they are used as slaves. For them, the only way out of this situation is to have a baby from a stranger while in service.

Midnight had just elapsed. Lula woke with a start following a bossy kick delivered by a rifle butt at her house’s door. Thus terrorized, she dashed out of her bed immediately. The soldiers surround a dilapidated two-floor building near the airport of Asmara. The girl quickly inserts a pant and a jacket, and before opening the door she turns a rapid look toward the desperate eyes of her mother. The officer, placed at the main door, snarls some sentence toward the women.

Lula hasn’t got the “menqesaqesi” (the military travel permit”). A man catches her violently by the arm and drags her to a truck already full of frightened boys and girls. In a few seconds the truck disappears in obscurity. Their destination is Sawa.

Sawa is an extremely severe and unapproachable military training camp situated in the red-hot desert near the border with the Sudan. The young Eritrean girls call it more simply “the rapes camp”. But they can whisper this only in your ear.

Sooner or later everybody is bound to go through Sawa. All the Eritreans between the age of 17 and 40 are obliged to go to Sawa. But, often, also teen-age boys and girls end up in it. The figures are spine chilling: it is calculated that over 200 thousand Eritreans, half of which women, have been recruited by force.

Lula started attending Sawa in January 2001. She is just 17 years old. She has left school in 1998 in order to look after her younger sister. Abandoned by the husband, her mother is a cardiopathic. It is now two years since she last heard from her two elder brothers. Most probably they perished, like the other 19 thousand youth (officially) declared dead, during the foolish war waged against Ethiopia in 1998.

For Lula the six months spent in that bloody camp are still a nightmare. She recalls: “At the beginning it was simply a torture. In silence, I put up with enervating marches in the desert, amid spiders and snakes, under a blinding sun that breaks your legs. I wanted to demonstrate to the “bosses“ that I am a good patriot. The suffering started 4 months later, when I was too tired to rebel.

Everyday, at the sunset, the male officers used to enter bossily inside our tents to choose one of us in order to spend the night with her. These officers, although duly married, considered it normal to go to bed every night with a different female solder. Very soon I got pregnant and as a result I was immediately sent back home”

The dramatic experience made in Sawa has meant for the young mother the abandonment of every hope in the future. “The government’s propaganda promises jobs to the youth completing the obligatory military service. But this is not true. Besides, the wage is only 150 nakfa per month more or less the equivalent to 7,5 euro at the black market. They prevent us from studying and by doing so they steal from us the capacity to have and realize our dreams. I do not know how, without a husband, I will be able to feed Stella once I am finished nursing her. One thing is certain, however. When her turn to go to Sawa comes, I will hide her. I will never allow my child to go to Sawa”.

Some catholic nuns, secretly, run a clinic for ex female solders. A lot of families refuse to welcome home the single mothers or the fugitives from Sawa. As a result, the nuns are the only bosom-friends of the young women thus traumatized or about to give birth to children conceived in military camps. “The situation is by now uncontrollable – declares a nun -. A lot of women marry ‘perfect strangers’ in order to avoid the ‘giffa’ (the forced roundaps). Some others cannot hold out and commit suicide. Ever since the government has decided not to recruit women with children anymore, our clinic is full of pregnant girls waiting to deliver the children they got from strangers. They then return in a desperate mood when they realize that without the military membership card they will never have a job. The future of this country is bleak, indeed”

Elsa, on the other hand, has completed her 18 months of military service. 12 of which near Assab: right in the middle of the hellish Dankalia desert. She shows faded photos of Sawa while proudly training in her uniform and smiling. “It was in 1998. I was 20 years old. After 6 months I realized the soldiers were expecting from me a different kind of ‘service’. My 17 years-old companion and I were made to settle in a house already occupied by male solders”, whispers Elsa. “In practice we had become theirs slaves. As a matter of fact, during the day we had to work for them for 12 hours and by night we were raped. It was simply an unbearable torment. I was fortunate enough to be chosen by an unmarried man. At the beginning I was happy, but he sent me back home in Asmara when I got pregnant. Luckily, this had happened 2 months before the burst of the war. Otherwise I would have been killed at the war front. The officer wrote to me a letter to disown the fatherhood of the child I was about to deliver. I know that in the meantime he had married another girl. A lot of my companions suffer from AIDS. We know about the existence of this disease, but I personally do not know well how one gets it”.

The spread of HIV virus in Eritrea is alarming. Only one case was reported in 1988. But in 2001 there were over 13 thousand patients. It is now growing at a rate of 3 thousand new victims every year.

The war between Eritrea and Ethiopia is by now over. 3500 peacekeeping solders of the United Nations, including 150 Italians, are making sure the ceasefire holds. President Isayas Afewerki had solemnly promised to demobilize around 150 thousand soldiers. The World Bank had allotted money for their studies and professional activities. Today, nobody speaks about this project anymore. Lurking at the street-corners, every night, teen-age solders wearing mimetic overall and sandals, order their same age groups to exhibit the hated “menqesaqesi”. Whoever is found without it, s/he is immediately sent to Sawa.

It is forbidden to speak of such thing as forced recruitments. The government prefers to calls it “summer work programs” or “maetot”. Beginning from June of this year combings have intensified. So much so that on Tuesday night of July 9 alone 3 thousand people were mopped up. In the evening the city of Asmara is almost desert. The young people that attend cafe and restaurants are only the Eritreans residing abroad who return home to spend the summer vacations. They are affectionately called by the population: “Beles” (“prickly pears”). In order to dodge round the forced recruitments the girls spend the night everyday in a different place. Or, as it is the case with those of them working in hotels, are hidden in the wine cellars of the same hotels duly equipped of mattresses and water. But, often, this is not enough. As a matter of fact, the army officers go directly to the employer to demand the hand over of his employees.

The raking system has provoked the paralysis of the economy and, as a result, a lot of enterprises have closed down. Should a water-tap drip, there are no plumbers to repair it; the arable land is neglected because there are no hands; the Ministry of Education was forced to hire 300 Indian teachers because the Eritrean teachers have either disappeared on the front or are sent to Sawa. President Isayas has never promulgated the 1997 Constitution. He ordered, instead, the arrest of 15 of his closest and experienced collaborators. They are jailed in a secret place. Their only fault was to have dared to write a letter asking for long awaited democratic reforms.

The free press has been suppressed and the journalists imprisoned. 400 university students who opposed the government’s “Summer Work Programme” have been sent to Wi’a with the assignment to pile up stones. Wi’a is a lager next to the seaport of Massawa where the temperature often exceeds 40 degrees. The other 1700 students too have been prevented from registering for the new academic year because blocked by the endless compulsory military service. To speak openly of the political and social situation of the country is impossible. As in the ’70 and ’80, fleeing the country has restarted. For example, to lot of women are escaping on foot to Ethiopia and the Sudan but also to other countries reachable by sea. Those who can pay are brought to the seacoast and made to settle down in a small boat in the middle of the Red Sea while waiting for a bigger boat or ferry in rout towards Europe to arrive. Others fall victims of swindlers without scruples.

In Eritrea the bonds with Italy are still very strong. A lot of Eritreans, including some young people, speak perfectly our language. Asmara gives hospitality to the most important Italian school abroad and its architecture (of the ’20) as well as the atmosphere one breathes is similar to that of a calm and drowsy city of south Italy. One evening I was in a restaurant. There, I met an Eritrean man of about fifty years old. In front of him there was a dish of steaming hot “tagliatelle” with meat sauce.

Although with some embarrassment, he volunteered to speak about his daughter. “She is 20 years old. She has completed the Italian school 2 years ago. Her grandmother, i.e. my mother, too was an Italian. She should have left for Sawa by now, but I got some false documents for her according to which it turns out to be still too young to go to Sawa”. What about going abroad? “It is impossible! No passport without the military enrolment card. The government has annulled all the scholarships too, because many students never return home. In the evening she doesn’t go out and the whole family is hiding her in order to avoid being sent to that aberrant military camp. But in this small country with about 3 and a half million inhabitants, there are no so many places left for hiding oneself”.

m. r.

This article was written in 2002 but is still up to date

Questo articolo si può leggere anche in italiano